(Guest post by Nancy McCabe and Emily Anderson, in conversation)

Nancy: One of the reasons I chose this chapter is that I’ve always found the relationship between Laura and Rose so intriguing. I grew up regarding everyone in Laura’s world as somewhat simpler and more virtuous than in my own. When I was a young adult and read Ghost in the Little House, it was a revelation to imagine a complex, conflicted mother-daughter bond, to see both Laura and Rose as more fully human. At the time I missed Holtz’s very critical portrayal of Wilder, I suppose because I was still identifying as a daughter rather than as a mother—and because it was such a relief to realize that she wasn’t perfect after all.

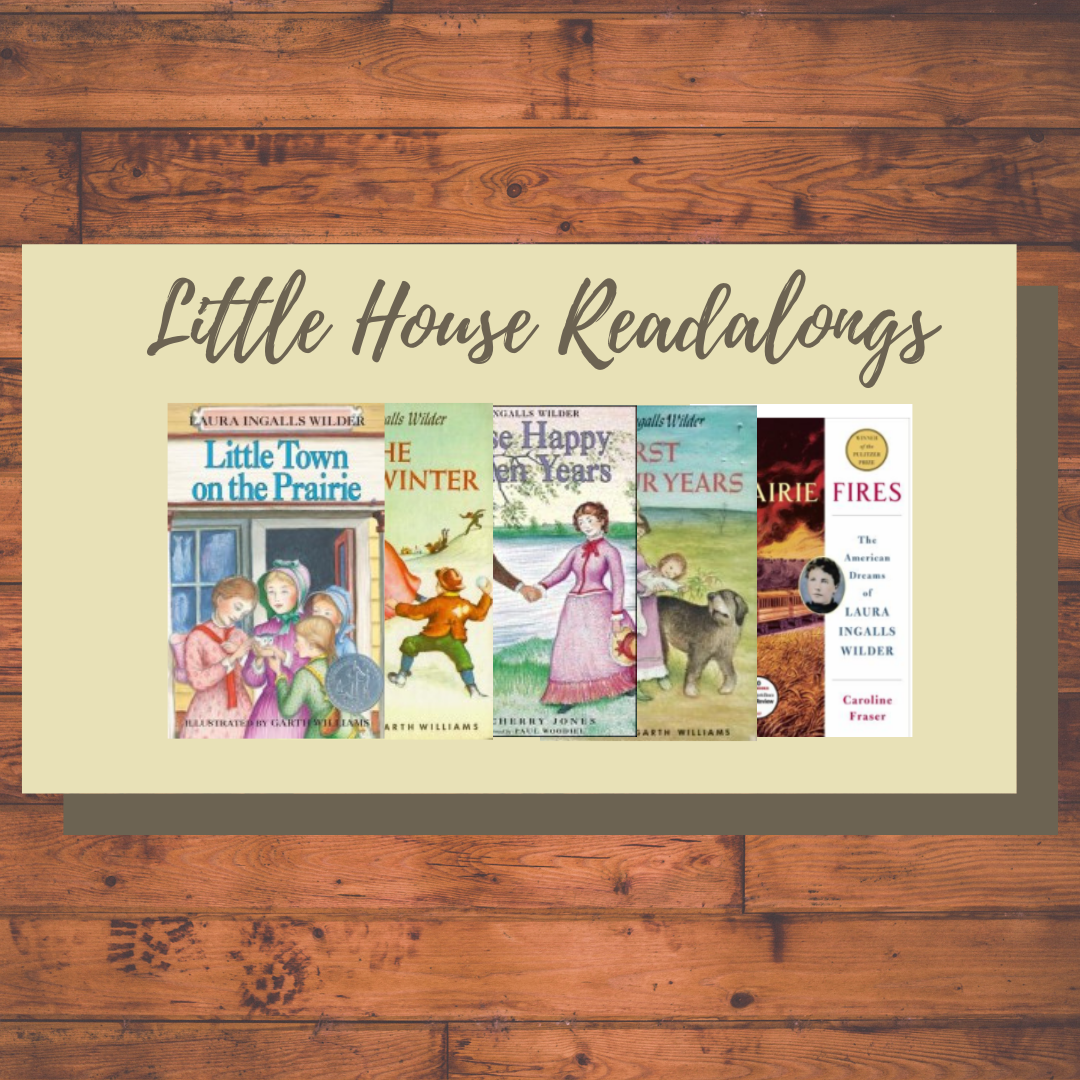

I loved how reading Prairie Fires—on the heels of reading Pioneer Girl—continues to deepen my understanding of the mother-daughter relationship. Recently, another Prairie Firesreader on a children’s literature e-mail listserv posed the question of whether Rose was “on the spectrum”—referring, I think, to the possibility that Rose wasn’t so much mentally ill as potentially not neurotypical. I couldn’t get this out of my head when I was reading this chapter of Prairie Fires. Certainly she appears to have had some difficulty with conventional social skills. And whatever the case, I’ve always resisted judging Rose too harshly though it does seem that dealing with her could be very trying. What do you think about this?

Emily: I agree—Rose is a challenging woman. But that’s why I’m drawn to her. Even today, women leaders are evaluated in terms of their “likability,” but Rose was successful, influential, and difficult to like. I love that!

At the same time, it’s clear that Rose had a difficult emotional life. I don’t know how (or if) psychologists might diagnose her today, but Rose herself was concerned about her mental health. She used the then-current medical term “manic depression” (today known as “bipolar disorder”) to describe her moods. She spent her adult life alternating between periods of exuberant planning and spending and periods of despair.

This optimism/despair pattern is part of Rose’s personal emotional make-up, but it also sounds a lot like the U.S. economy of the 1920s and 1930s. The Roaring Twenties, a spending blitz, slumped into the Depression. The stock market crash of 1929 was a dramatic example of the boom-and-bust cycles that characterize capitalist economic systems. Gold rushes become ghost towns. Logging booms become felled forests. We live in a world where people are always looking for the next big thing—because the current big thing is bound to crash. I don’t know whether Rose had a mental illness, but I suspect Rose’s moods had something to do with her restless belief in the American dream, which inspired her to quest after the next big thing, yet never allowed her to experience a feeling of security.

Nancy: I love the way you put Rose’s behavior in a historical context, which seems to me to be a much wiser route than trying to diagnose her in retrospect, always a precarious undertaking. What interested you about this chapter?

Emily:I liked Fraser’s depiction of the melancholy, nostalgic nature of Wilder’s work—the idea that Wilder was trying to put back together a past that had been fractured. Do you experience Wilder’s work as melancholy? Do you think nostalgia appeals to child readers?

Nancy:The nostalgic vision in Wilder’s work appealed tremendously to my own mother and aunts, who grew up relatively poor down the road from Rocky Ridge during the 1930s and, I think, felt that the Little House books offered a kind of mythology for their own somewhat austere childhoods. Their father had arrived in that region as a boy in a covered wagon, and they lived in a small wood frame house insulated by old newspapers. Their father had his own struggles with supporting the family. Wilder’s books offered a lens that softened their memory of hardship. The books’ nostalgia for simplicity, for an unencumbered life centered on family, nature, music, was certainly part of what led me as a child to see Wilder’s world as far less dimensional than the way I see it today. My mother and aunts regarded any questioning of that mythology to be sacrilegious, and to this day it feels to me pleasantly transgressive to look at Wilder’s work from other points of view—that’s one of the joys of Wilder scholarship for me, and something that attracted me to Prairie Fires.

But while I appreciate new perspectives that feel more aligned with my own worldview than that presented to me by my mother and her sisters, I’m still drawn to that nostalgia. The first time I reread the Little House books as an adult, I was especially struck by the repetitions of words like “happy,” “cozy,” “pretty,” “snug,” and “sweet,” and felt a great sense of gratitude for small pleasures. To me what makes Wilder’s work great, though, is her ability to manage nostalgia without sentimentality—and also because of that melancholy that strikes me as a very real strain that runs underneath, both fueling and destabilizing the nostalgia. I may have seen these books as simple at one time, but now, thinking about Fraser’s discussion of nostalgia and melancholy, I see that the complexity was there all along. One of Fraser’s examples is Laura’s wedding, “among the most melancholy and subdued . . . in children’s literature,” informed by the “storms of ill fortune” to come. This is all subtextual, of course, because, as Fraser says, “Children had to be protected from the truth.” The truth is, to me, such a relief. I remember feeling, vaguely, that books like these were sort of gaslighting me, making me doubt my own vision of reality. The world I lived in felt so much more flawed.

Emily:I love your point about the emotional complexity in Wilder’s relatively spare wedding chapter. As a child reader, I felt that Laura’s wedding marked the “end” of the Laura books (I never really connected with The First Four Years). So Laura’s black wedding dress was, to me, funereal: Laura’s wedding was the end of Laura. There was no more Laura after that. At the same time, concluding the books with a wedding gave me fascinating, frightening sense that life has rigid, yet meaningful, boundaries. You close one door, and it stays shut. You step into a new destiny, and there’s no going back.

I think, as a kid reader, I expected my life would be like Laura’s. I would advance in a sequential way from life stage to life stage, the way the pioneers settled the frontier—in stages. I would experience a sense of progress. But that isn’t how I have experienced my adult life. I wonder if “adulting” feels disappointing because adulthood is mostly wandering in the wilderness, not knowing where you’re going, or if things are going to be okay, or if progress exists at all. Adulting feels much more like the disorderly narrative in Pioneer Girl—Ma and Pa trying to run a hotel, and that not working out, and then trying to farm, and that not working out—than it does in the novels Rose and Laura worked on together.

Where do you see the connection of Wilder and Lane’s writing, with your life?

Nancy:As a writer of memoir and the parent of a child of color, I’ve often grappled with debates about who “owns” life experience, who has the “right” to write about what. I believe on the one hand that we have to be careful of appropriation that furthers stereotypes, while on the other hand our literature is enriched by multiple perspectives on the same experience. So I’m uncomfortable at discussions that imply that Rose “stole” her mother’s material, particularly in writing Let the Hurricane Roarand then Free Land. It seems to me natural that a writer would draw from the stories that she’d been told about her ancestors and the stories from her parents’ lives that had impacted her own; it’s the way that writers make sense of their own heritage.

There are probably many factors influencing Laura’s feeling of betrayal by Let the Hurricane Roar, and I was interested in Fraser’s discussion of how she expressed greater enthusiasm for Free Land. Laura herself was telling others’ stories—her own parents’, Almanzo’s. Was that different because her parents were dead by then, or because, while Fraser mentions that Caroline wrote poetry (a surprise to me), she was an unpublished writer? This made me think a lot about those lines between appropriation and appreciation.

Emily:One of my favorite parts of the novels is when Pa (or someone) cracks a joke and it’s so funny that “even Ma smiles.” I picture Ma as this incredibly stoic person. So I love the idea that she was a poet! At the same time, I’m not surprised—she had that pearl-handled pen, after all.

What Rose did, in my opinion, was savvy marketing. I think she was way ahead of her time, and would have thrived in a 21stcentury literary marketplace. Today, we see in our movies, TV and books a tendency toward spin-offs, sequels, prequels, etc. Interlinked books contribute to a brand identity that can boost sales. Authors today are expected to “grow a platform” (build an audience) and grow their “personal brand.” In doing so, the line between “writing literature” and “marketing literature” gets blurry. Today we often call writing “content creation,” which encapsulates both the commercial and the literary aspects of a highly commercialized art form.

To keep pace with the ceaseless demand for “content,” writers often recycle, riff off, or remix existing work–and that’s exactly what Rose did.

I don’t think such a ruthlessly commercial world is the ideal world for writers, or for literature– but Rose and Laura were nothing if not survivors. The tactics they used to build their brand have helped perpetuate their legacy and enabled me to enter the world of Little House, and for that, I’m thankful!

Nancy:On a lighter note, do details like the fact that Wilder gave her character much better test scores than she herself made change your notions of the series, if at all?

Emily:I loved learning about Laura’s low grade (69) in history! So funny that a writer whose books have come to be regarded as history was a D+ history student herself. History and government are crucial facets of the novels, and were clearly important dimensions of Laura and Rose’s lives. I loved the part in Prairie Fires when Rose and Laura send around a chain letter encouraging friends to write their Congressmen in support of “America First” foreign policy. The chain letter reminded me of political memes people might share on Facebook today. What do you think Rose’s Facebook presence would be like today? Laura’s?

Nancy: I can envision Rose’s tweets: things like “AN ARMY OF PRINCIPLES WILL PENETRATE WHERE AN ARMY OF SOLDIERS CANNOT!!!” I picture a younger Laura posting status updates on Facebook like, “Mary lost her sight today, but she is so brave and has never once repined,” or a photograph of her Christmas gifts—a candy cane, a little cake, and a shiny penny with the caption, “There has never been such a Christmas!” I can see social media exaggerating that sense of inadequacy I had as a child because my life didn’t seem to measure up to that of those grateful, uncomplaining pioneers.

Really, though, I think the adult Laura would probably post wise, lyrical observations. And photographs of her chickens.

Comments3

What an absolutely brilliant post. I’ve had many of these thoughts while reading Prairie Fires, which I consider an extremely fine book but one that troubles me with its evident mission to over-portray Rose as mentally ill. It’s wonderful to see two such thoughtful writers discussing this at such a high and sophisticated level. Thank you!

Thank you, Diana!

I have often wondered if Rose was on the spectrum. Any thoughts from others on this?

Comments are closed.